A large part of the Canadian presence at MIFA this year comes in the form of two apprenticeship programs piloted by the National Film Board of Canada: Hothouse and Alambic.

To better understand what’s in store for festival and market attendees, we spoke with Anne-Marie Bousquet, who oversees the Alambic program, and Maral Mohammadian, who oversees the Hothouse program.

Answers have been condensed for length.

Can you tell me a bit about the mentorship programs you oversee?

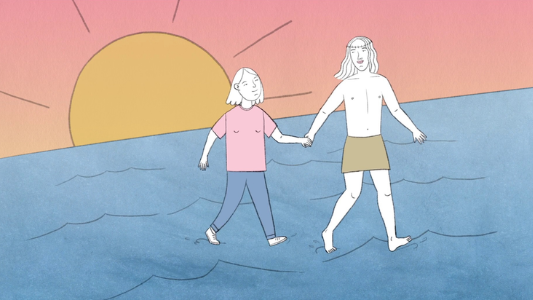

Maral Mohammadian (MM): The NFB English Program has an apprenticeship program called Hothouse, designed specifically for emerging animation filmmakers.

It’s a professional production program where participants make a one-minute film over a period of three months, typically, from concept to completion, with support from mentors and within the NFB’s culture of auteur animation filmmaking.

This is not ‘quick and dirty’ but rather ‘intense and amazing’—think of horticultural hothouses, where gardeners create optimal growing conditions to encourage the blossoming of exotic blooms in weeks instead of months.

Hothouse is open to emerging Canadian creators across the country. It’s generally limited to six candidates who can work with a professional crew and hone their craft and their voice as filmmakers. Our goal is to support new voices in this field, with an emphasis on the role of the NFB as a creative producer and a distributor. It’s a sort of prototype experience for a bigger collaboration afterwards, but alumni also go on to do indie films or work in the industry.

The program has become a renowned and highly celebrated means of talent discovery and has helped spawn a vibrant generation of animation filmmakers in Canada, with 79 alumni to date. Founded in 2003, Hothouse was designed by the Animation Studio’s then executive producer David Verrall alongside producer Michael Fukushima. We recently completed the 13th edition under the NFB’s new structure of the Animation and Interactive Studio.

Anne-Marie Bousquet (AMB): I’m in charge of the Alambic program. It’s a new initiative dedicated to the newest generation of animators. After twenty-three editions of the Cinéastes recherchés contest, the animation studio in the NFB’s French program wanted to shuffle the cards and try a new approach to reach the newest generation of francophone animators. Alambic is a creative laboratory that allows three emerging director-artists of any age to create an animated short of 45 seconds to two minutes over a six-month period. Alambic favours a spirit of community and collaboration. All production and content meetings are held with every filmmaker sitting at the same table. This allows them, in a way, to participate in the other two artists’ work, to learn about each other, to encourage each other and ultimately deliver the best of themselves. Throughout the project, the filmmakers are surrounded by the studio’s team, by an experienced consultant and by other rising animators. The goal is for them to take advantage of this experience by building a network of partners and contacts for future projects.

The word alambic (or still, as in the distillation process) as the name of this initiative refers to a boiling pot of creativity, where ideas mix together and imagination is distilled, drop by drop, in order to help us better learn about the essence of these new talents.

What does it mean to you to be part of this festival and/or market? What are the benefits of such a presence?

MM and AMB: For the Alambic and Hothouse cohorts, it’s a great prolongation of their participation in this initiative meant to support the next generation. Their participation in festivals and markets is an occasion for them to continue the approach begun in production by giving them the opportunity to showcase their work, their vision, their talent and to develop a network that will certainly help them accomplish their professional goals.

Canada has always had an excellent international reputation when it comes to animation. How is the industry faring now?

MM: It seems to me the industry is thriving now. The pandemic hit the live-action industry quite hard, whereas animation production was generally able to continue without too much disruption. Apart from large-scale stop-motion that requires on-set crews and lots of physical assets, most animation can be done in isolation (animators make many bittersweet jokes about this fact). Most animators work digitally and are used to virtual pipelines and remote work. Those who work analogue can do so in modest spaces and setups.

AMB: We can also observe an increase in the number of private production companies that decide to start new animation projects. The democratisation of tools and their increased availability also allows many directors to work on projects by themselves, in a completely independent fashion.

What characterizes the newest generation of animators?

AMB: I think the new generation is doing very well; they’re beautiful and committed. I think what characterizes it is this need to engage conversations and tell their stories in their own manner. I have to say that the network of animation schools in Quebec and Canada is excellent. It’s immediately noticeable in the quality of student films that we can watch at festivals and online.

MM: I’m noticing that the next generation of animation creators in Canada is distinctly conscientious. They are intentional about who they are and their place in the world. When it comes to the craft, they are nimble, collaborative. It used to be normal for someone to spend five to seven years on a animated short film (because Every. Thing. Takes. So. Long); but people don’t want to do that anymore. They want more immediacy in their craft, so they seek out the means to have that. They also have a very natural relationship with image-making in general: they make and share work daily, so they’re more fluent about the exchange that happens with artistic work designed for a public. I think (and hope) that all this means animation is becoming more accessible to people who wouldn’t otherwise study it formally. Animation is very technical, so it’s intimidating or outright inaccessible to a lot of people. But ease of use via technology and an image-obsessed culture (for better or worse) is making it possible for more people from various walks of life to play in this sandbox.

Can you tell us a bit about the projects that will be in Annecy?

MM: The NFB is participating in this year’s Annecy International Animation Film Festival with three short films in competition: the much-anticipated world premiere of The Flying Sailor, by acclaimed filmmakers Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis (produced by David Christensen); Meneath: The Hidden Island of Ethics, by award-winning Orkney Cree Métis artist Terril Calder (produced by Jelena Popović); and Magical Caresses: Sweet Jesus by young director Lori Malépart-Traversy (produced by Julie Roy and Christine Noël). The NFB and its animation studios will be featured at the festival’s Studio Focus, an in-person event taking place on June 14, shining a spotlight on projects that are currently in the works. For this Studio Focus session—the first to be held in-person—the NFB will showcase its programming vision, which is more dedicated than ever to new forms of storytelling, through the voices of the creators whose projects were selected for Annecy 2022.